- Sinthia Cousineau

- Ceramic Art

- Drawings

- Paintings

-

Photography

-

Art Education

-

Art & Adolescence

>

- Mural Project >

- Lesson: Eco Art

- Lesson: Decorating Fabric

- Lesson: Zentangles & Patterns

- Lesson: Social Media, consumerism & war

- Lesson: Bag Sculptures & Positive Body Image

- Lesson: Caricatures & political activism

- Lesson: Canadian Landscapes & Group of Seven

- Tattoo Art & Meaningful Images

- Lesson: Stenciling Street Art

- Lesson: Plaster Figures (grade 7-9)

- Photoshop Lesson

- Lesson: Value Scales

- Lesson Plan: Video Art

- Lesson Plan: Sound Art

- Lesson: GIF Project

- Lesson: Mashup Videos

- Art Education & Older Adults >

-

Art & Children

>

- Collage & other art Activities >

-

Drawing Activities with Kids

>

-

Pencil, Markers and Coloring

>

- Introductory Lesson

- Introduction Lesson: Egyptian Name Cartouche

- Reptile Zentangle Drawing >

- Illustrated Names

- Symmetrical Name Creatures

- Drawing from Autumn Still-lives

- Grid Drawing Technique

- Lesson: Alliteration Drawing

- Drawing: 3D Hands

- Leaf Drawing Collage

- Ancient Egypt Art

- Collaborative Doodle

- Drawing: Hidden Emotions Behind the Mask

- Scribble Drawing

- Drawing : Word Art

- Lesson Plan: Renaissance Invention Scroll

- Lesson: La Bande Dessinée

- Lesson: Optical Illusions

- Oil Pastels >

- Chalk & Soft Pastel >

- Charcoal >

-

Pencil, Markers and Coloring

>

-

Painting Activities with Kids

>

-

Acrylic Painting Lessons

>

- Acrylic Pouring

- Australian Dot Painting

- Blow Paint Technique

- Bubble Wrap Painting: Bee

- Pointillism Painting

- Funky Easter Rabbit

- Lesson: The Color Wheel

- Monochromatic Painting

- Painting: Birch Tree

- Leaf Painting

- Pumpkin Painting

- Painting: Rock Painting

- Squeegee Painting Technique

- Origami Inspired Painting

- Coffee Art

- Watercolor Activities >

-

Acrylic Painting Lessons

>

- Mixed Media Activities with Kids >

- Types of Art >

- History Lessons

-

Art & Adolescence

>

-

Art Therapy

- 3D Art & other mediums

- Videos

- Contact Me

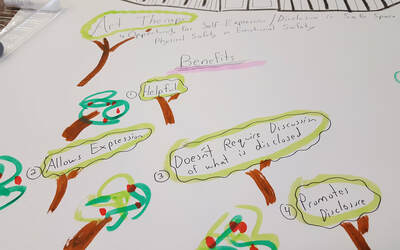

The Role of Art in Prisons

Art Therapy Benefits in Prison:-Helpful

-Allows Expression

-Doesn't require discussion of what is disclosed

-Promotes Disclosure

-Bypassing unconscious and conscious feelings and defenses

-Diminish pathological symptoms without verbal interpretation

-Supports creativity activity and provides emotional support

-Permits inmates to express themselves in an acceptable manner

-Allows Expression

-Doesn't require discussion of what is disclosed

-Promotes Disclosure

-Bypassing unconscious and conscious feelings and defenses

-Diminish pathological symptoms without verbal interpretation

-Supports creativity activity and provides emotional support

-Permits inmates to express themselves in an acceptable manner

The Role of Post-Secondary Art Education in Prisons

By Sinthia Cousineau

When one thinks of art, we think of freedom of expression, a world free of any constraints as creativity can lead us anywhere. When one thinks of prison, we think of a restricted environment, colourless jail cells, strict schedules and barbed wires. In many ways art and prison are complete opposites. Although they do not appear to have much in common, art does play a central role in a prison setting. Who is to say that prisoners are not entitled to freedom of expression? Although there freedom may indeed be restricted, art education does play a role in helping ex-offenders develop their creative side and reintegrate into society. This paper will focus on the role that art education plays in a prison setting.

The topic of art education in a prison setting will be discussed as relevant to Margaret Giles article titled “The role of art education in adult prisons: The Western Australian experience”. Giles (2016) aims to explore the importance that art education plays in adult prisons. She aims to establish whether art education contributes to improved labour market outcomes, whether it reduces recidivism, and whether it decreases the chances of re-imprisonment. She also aims to address the issue that if art education does not contribute to these factors, then why should art education courses in prisons continue to be funded. Her paper focuses primarily on addressing these issues based on a study that took place in an Australian prison.

The topic of art education in a prison setting will be discussed as relevant to Margaret Giles article titled “The role of art education in adult prisons: The Western Australian experience”. Giles (2016) aims to explore the importance that art education plays in adult prisons. She aims to establish whether art education contributes to improved labour market outcomes, whether it reduces recidivism, and whether it decreases the chances of re-imprisonment. She also aims to address the issue that if art education does not contribute to these factors, then why should art education courses in prisons continue to be funded. Her paper focuses primarily on addressing these issues based on a study that took place in an Australian prison.

According to Giles (2016), incarceration costs in Australia are very high. In fact, the average prisoner in Australia costs an average of AUD 15,000 per year. With the goal of helping the prisoners become better members of society, many prisons are involved in implementing correctional education resources to improve the labor market outcomes and prevent re-imprisonment. Correctional education could include vocational training, basic adult education and art studies. Due to the reality of prisoners being very expensive to accommodate, it makes good sense to ask why should one bother to fund art education programs for criminals, and whether that money could be best spent elsewhere, for instance on the non-criminal population.

A lot of research studies have been done to address this topic over the years. According to the literature review done by Giles (2016), it is reported that ex-prisoners who studied during their incarceration tend to recidivate less after their release. Now this applies to both art and non-art courses. Past studies indicated that outcomes tend to be best for prisoners who enrolled in classes that included vocational training. It was proven that education makes individuals less impatient and more opposed to taking risks. Although not many studies had access to post-release employment information for ex-prisoners, but of the few who did it was stated that that there was a link between prison study and both recidivism and port-release employment. Many of the studies examined by Giles (2016) showed that the effect of correctional education on reduced re-imprisonment was not necessarily linked to ex-prisoners finding employment.

A lot of research studies have been done to address this topic over the years. According to the literature review done by Giles (2016), it is reported that ex-prisoners who studied during their incarceration tend to recidivate less after their release. Now this applies to both art and non-art courses. Past studies indicated that outcomes tend to be best for prisoners who enrolled in classes that included vocational training. It was proven that education makes individuals less impatient and more opposed to taking risks. Although not many studies had access to post-release employment information for ex-prisoners, but of the few who did it was stated that that there was a link between prison study and both recidivism and port-release employment. Many of the studies examined by Giles (2016) showed that the effect of correctional education on reduced re-imprisonment was not necessarily linked to ex-prisoners finding employment.

Giles (2016) describes the major advantages of art education in the Western Austrian prison setting. The first advantage being that art education helps inmates develop and cultivate their creative talents. Secondly it helps ex-offenders unlock their potential to find jobs, and further their education which as a result helps them reintegrate back into society.

Creativity, self-expression, and a greater sense of self-worth and competence are among the important benefits of learning art. Prison art programs offer inmates an opportunity to further their studies and practice their art with the guidance of professional artists who provides them with the necessary supplies and equipment. It is through the artistic process that one gains an understanding of self and the world they live in (Brewster, 2015).

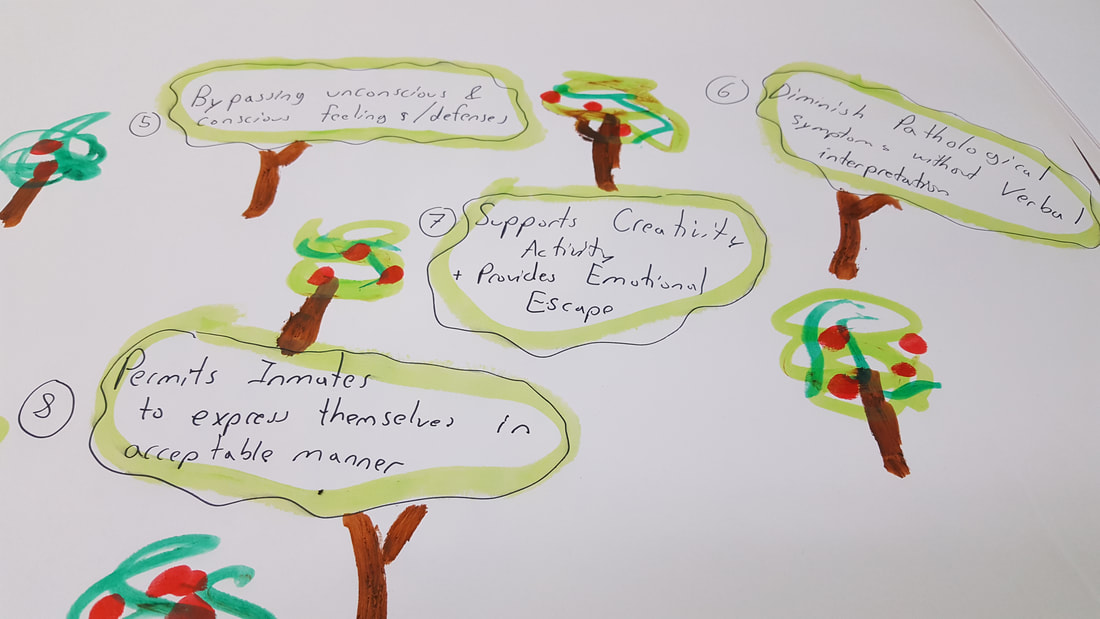

Art education has many advantages in a prison setting some of which are similar to the advantages of art therapy. There is however a different between art therapy and art education. Giles (2016) describes the difference being that art therapy is part of the behaviour management program, while art education aims to provide inmates with skills. Art is often expressed in a prison setting due to its therapeutic values as Giles describes ““There seems to be a natural tendency for artistic and creative expression in prison settings…evident in prison craft shops, murals, and intricately designed tattoos” (Giles, 2016, p. 693). Art education places more emphasis on the acquisition of skills. This is described by Giles (2016) when she states that. “The experience of learning to create art can build civic and social awareness, enhance self-esteem, and reprogram otherwise habitually negative patterns of thought and behavior” (Giles, 2016, p. 693).

Creativity, self-expression, and a greater sense of self-worth and competence are among the important benefits of learning art. Prison art programs offer inmates an opportunity to further their studies and practice their art with the guidance of professional artists who provides them with the necessary supplies and equipment. It is through the artistic process that one gains an understanding of self and the world they live in (Brewster, 2015).

Art education has many advantages in a prison setting some of which are similar to the advantages of art therapy. There is however a different between art therapy and art education. Giles (2016) describes the difference being that art therapy is part of the behaviour management program, while art education aims to provide inmates with skills. Art is often expressed in a prison setting due to its therapeutic values as Giles describes ““There seems to be a natural tendency for artistic and creative expression in prison settings…evident in prison craft shops, murals, and intricately designed tattoos” (Giles, 2016, p. 693). Art education places more emphasis on the acquisition of skills. This is described by Giles (2016) when she states that. “The experience of learning to create art can build civic and social awareness, enhance self-esteem, and reprogram otherwise habitually negative patterns of thought and behavior” (Giles, 2016, p. 693).

The history of post-secondary adult art education in prisons began in the 1960s to 1970s. In this time correctional education was considered a waste of time and tax payers’ money. People were skeptical of the benefits of art on prisoners, and believed it was a wasted effort. However Giles (2016) states that since 1974 any ex-prisoner who studied during the time of their incarceration tended to recidivate less after their release. It appeared that outcomes were best for prisoners that were enrolled in classes which incorporated vocational training. Education was also observed to make individuals less impatient and more risk-averse. Most of the studies examined by Giles (2016) showed that the majority of pat research has found that correctional education reduced re-imprisonment, but that was not actually due to ex-prisoners finding employment as previously stated. Therefore could art studies have been this contributing factor? Prison-based community college academics and vocation programs, as well as fine arts instruction are considered critical steps in the direction of preparing inmates for life after prison. These programs also help relieve tension and improve the behaviour of prisoners while they are incarcerated (Brewster, 2015).

The literature review conducted by Giles (2016) also determined that few studies actually had access to post-release employment information for ex-prisoners. Most of the qualitative research in the studies examined found that art creation allowed learners to master’s skills, materials, and techniques, to express abstract ideas and become visually literate. Past studies have also shown that art studies have other advantages on prisoners. For instance it can lead to an increase in civic and social awareness. It also can help differentiate between self and others as well as differentiate between present and past selves. It helps to reduce negative patterns of thoughts and behaviors. Lastly it has a tendency to increase self-esteem and self-worth.

The literature review conducted by Giles (2016) also determined that few studies actually had access to post-release employment information for ex-prisoners. Most of the qualitative research in the studies examined found that art creation allowed learners to master’s skills, materials, and techniques, to express abstract ideas and become visually literate. Past studies have also shown that art studies have other advantages on prisoners. For instance it can lead to an increase in civic and social awareness. It also can help differentiate between self and others as well as differentiate between present and past selves. It helps to reduce negative patterns of thoughts and behaviors. Lastly it has a tendency to increase self-esteem and self-worth.

Due to the fact that Giles (2016)’s study focuses on Western Australian prisons, her research method incorporated the use of the Western Australian Prisoner Education and Welfare dataset. This dataset examined over 14, 643 prisoners and ex-prisoners that were incarcerated in an adult public prison between the period of July 1st, 2005 to June 20th, 2010. In the data examined sixty-five percent of prisoners had only one recorded prison term while 34% had two or more prison terms. The date involved in the research methodology for this study did not include information about a prisoner’s prior education or work history. Most of the information in this study was collected with self-report and interviews with the prisoners.

This study may be considered to have some selection bias in the profiles of the prisoners who decided to study. This is due to the fact that there is a difference between prisoners who study and prisoners who do not study. The dataset showed that there are more male prisoners then female prisoners who chose to study. Prisoners who are between the ages of twenty-six to forty years old are more likely to study then prisoners below or over that age group. Prisoners from a non-metropolitan region are more likely to study, and so are indigenous prisoners. Lastly, prisoners with a longer prison sentence and more prison terms also more likely to take classes (Giles, 2016).

When considering art studies in Australia these generally require a diploma and associate degree courses and tend to be more conceptually orientated. Post-secondary art studies in Australia usually aims to develop advantaged aesthetic sensitivities, visual literacy skills, an experience with high-end studio practice, the ability to perform complex critical analysis, and give a personal voice and an ability to respond to issues of the world. Degree programs in art for prisoners involve studio practice and art appreciation with the goal of training these prisoners to come visual artists and art professionals. An advantage of the graduate diploma pathway offered to prisoners is a chance to enter a teaching profession as a specialist art teacher. Art classes in prisons usually overs one term, and in Australia a term covers a period of ten weeks. Prisoner-students a term described by Giles (2016) as a prisoner who studies during their incarceration are also able to re-enroll in the same class or unit as many times as they like to develop their learning and acquire techniques and competencies.

This study may be considered to have some selection bias in the profiles of the prisoners who decided to study. This is due to the fact that there is a difference between prisoners who study and prisoners who do not study. The dataset showed that there are more male prisoners then female prisoners who chose to study. Prisoners who are between the ages of twenty-six to forty years old are more likely to study then prisoners below or over that age group. Prisoners from a non-metropolitan region are more likely to study, and so are indigenous prisoners. Lastly, prisoners with a longer prison sentence and more prison terms also more likely to take classes (Giles, 2016).

When considering art studies in Australia these generally require a diploma and associate degree courses and tend to be more conceptually orientated. Post-secondary art studies in Australia usually aims to develop advantaged aesthetic sensitivities, visual literacy skills, an experience with high-end studio practice, the ability to perform complex critical analysis, and give a personal voice and an ability to respond to issues of the world. Degree programs in art for prisoners involve studio practice and art appreciation with the goal of training these prisoners to come visual artists and art professionals. An advantage of the graduate diploma pathway offered to prisoners is a chance to enter a teaching profession as a specialist art teacher. Art classes in prisons usually overs one term, and in Australia a term covers a period of ten weeks. Prisoner-students a term described by Giles (2016) as a prisoner who studies during their incarceration are also able to re-enroll in the same class or unit as many times as they like to develop their learning and acquire techniques and competencies.

Another topic Giles (2016) addresses in her article is who teaches art in prisons, and what are the requirements to be able to teach art to prisoners? In Western Australia prison art teachers are able to teach if they meet certain requirements. First they are professional artists with a Certificate IV in training and assessment. This is the minimum requirement to be able to teach in Australia. Art teachers can also be university-trained with a four-year teaching degree with an art studies specialization or have completed a three-year undergraduate degree in art studies with a one year diploma in education. One advantage of being an art teacher in Australia is they can also provide educational counseling for prisoner students and can enroll students in art studies classes following referrals of prisoner-students from other staff members. According to Giles (2016) art education for prisoners is used as a gateway to more formal study or vocational training.

Prison art education have also shown that art educators play an important role not only in teaching, but they also serve as important mentors, especially for the inmates who when they were children struggled in school. Inmates tend to form a positive relationship with wither art instructions because they experience the instructor as an artist and not an authority figure. Art educators in prisons play an important role in encouraging their students to advance their education (Brewster, 2015).

Art and prisons although very opposite of each other can work harmoniously together. Giles (2016) proves this when she brings up the example of the Fremantle prison in Western Australia. This prison was decommissioned in 1991, and today it is known as a World Heritage site to which it was officially declared in 2010. It is now used as a tourist attraction with a museum and art gallery spaces. The western Australian department of corrective services uses this gallery space now to exhibit artworks made by prisoners, and holds four exhibitions per year. In fact prisoners who take art studies courses or are involved in art therapy activities are eligible to exhibit and sell their artwork.

Prison art education have also shown that art educators play an important role not only in teaching, but they also serve as important mentors, especially for the inmates who when they were children struggled in school. Inmates tend to form a positive relationship with wither art instructions because they experience the instructor as an artist and not an authority figure. Art educators in prisons play an important role in encouraging their students to advance their education (Brewster, 2015).

Art and prisons although very opposite of each other can work harmoniously together. Giles (2016) proves this when she brings up the example of the Fremantle prison in Western Australia. This prison was decommissioned in 1991, and today it is known as a World Heritage site to which it was officially declared in 2010. It is now used as a tourist attraction with a museum and art gallery spaces. The western Australian department of corrective services uses this gallery space now to exhibit artworks made by prisoners, and holds four exhibitions per year. In fact prisoners who take art studies courses or are involved in art therapy activities are eligible to exhibit and sell their artwork.

Fremantle Prison in Western Australia

Giles (2016) was interested in comparing the date from prisoners and the classes in which these prisoners enrolled in. First she compared the profile and outcomes of studying prisoners who enrolled in one of more art studies class to those who did not enroll in any art studies class. Secondly she would compare enrolments with non-art class enrollments.

The study yielded some interesting results that show the impact art studies can have on a prison setting. For instance the study determined that at least fifteen percent of prisoners enrolled in at least one art studies class. There was also a difference in gender as the study determined that more female then male prisoners studied art. In fact there were twenty-three percent of female prisoners studying art and thirteen percent of male prisoners studying art. This is perhaps due to the limited curriculum available to the female prisoners when compared to male prisoners. The study also showed that middle-aged prisoners who chose to study were more likely to enroll in art studies classes at sixteen percent then compared to younger and older prisoners at thirteen percent. Prisoners who originally had resided in rule Western Australia were more likely to have enrolled in some art studies classes then who resided in a metropolitan area. In fact the study showed that eighteen percent of these students who enrolled in art classes were from rural areas whilst twelve percent were from urban areas. Prisoner-students who had studied before were twice as likely to end up choosing an art studies class. This study also determined that school completion and student attendance was significantly poorer for rural students and aboriginal students than those from the metropolitan area. Another interesting result is that prisoners who took education and training classes and had a longer sentence, of more than one prison term were also more likely to enroll in art studies class. Fewer art classes were successfully completed at forty-one percent compared to non-art classes at sixty-two percent. Most of the prisoners who did first enroll in an art class would later enroll in other classes. Prisoners who started by studying at least one art class would continue to study art, but the students who started by studying non-art classes were unlikely to start studying art later. Actually the results would show that seventy-four percent of the prisons who studied art had also enrolled in adult basic education programs later (Giles, 2016).

The study yielded some interesting results that show the impact art studies can have on a prison setting. For instance the study determined that at least fifteen percent of prisoners enrolled in at least one art studies class. There was also a difference in gender as the study determined that more female then male prisoners studied art. In fact there were twenty-three percent of female prisoners studying art and thirteen percent of male prisoners studying art. This is perhaps due to the limited curriculum available to the female prisoners when compared to male prisoners. The study also showed that middle-aged prisoners who chose to study were more likely to enroll in art studies classes at sixteen percent then compared to younger and older prisoners at thirteen percent. Prisoners who originally had resided in rule Western Australia were more likely to have enrolled in some art studies classes then who resided in a metropolitan area. In fact the study showed that eighteen percent of these students who enrolled in art classes were from rural areas whilst twelve percent were from urban areas. Prisoner-students who had studied before were twice as likely to end up choosing an art studies class. This study also determined that school completion and student attendance was significantly poorer for rural students and aboriginal students than those from the metropolitan area. Another interesting result is that prisoners who took education and training classes and had a longer sentence, of more than one prison term were also more likely to enroll in art studies class. Fewer art classes were successfully completed at forty-one percent compared to non-art classes at sixty-two percent. Most of the prisoners who did first enroll in an art class would later enroll in other classes. Prisoners who started by studying at least one art class would continue to study art, but the students who started by studying non-art classes were unlikely to start studying art later. Actually the results would show that seventy-four percent of the prisons who studied art had also enrolled in adult basic education programs later (Giles, 2016).

According to Giles (2016) there are two factors that measure the success in prison education. These two factors that determine whether a prisoner’s education was successful are improved labor markets and reduced recidivism. Improved labor markets are measured by workforce participation, employment and occupation. Prisoners who are released after their incarceration are generally given unemployment benefits. This study determined that ex-prisoners who were enrolled in an art class when incarcerated would remain on the unemployment benefit for one third of the period of availability which is twenty days of the sixty-two days the benefit grants them. However ex-prisoners who had enrolled in non-art subjects classes would have used up these unemployment benefits within a period of six days.

Giles (2016) describes recidivism as re-incarceration within the three years following the release of the prisoner. What is interesting with the results of this study is that the rate of re-incarceration for prisons who took art classes was higher than the rare of re-incarceration for prisoners who took non art subjects. In this the rate for prisoners who took art classes was fifty-six percent and those who took non-art classes was fifty-one percent. This result may have been due to the prisoner’s poorer education histories to enroll in an art class.

Giles (2016) describes recidivism as re-incarceration within the three years following the release of the prisoner. What is interesting with the results of this study is that the rate of re-incarceration for prisons who took art classes was higher than the rare of re-incarceration for prisoners who took non art subjects. In this the rate for prisoners who took art classes was fifty-six percent and those who took non-art classes was fifty-one percent. This result may have been due to the prisoner’s poorer education histories to enroll in an art class.

This study showed interesting results, which makes one wonder if statistics are similar for Canadian prisons and whether art courses in Canadian prisons would have yielded the same results as art courses in Australian prisons. One weakness of this study is it applies only to Western Australia and not the world in general. Also this prison focuses more on the public section then the private section. Another weakness of this study is it failed to give examples of what kind of art lessons were taught in the courses and which of these lessons were the most beneficial.

Art in prisons can also be considered a leisure activity for the inmates. Art studies programs have an important goal to provide prisoners with a constructive leisure-time activity to help them relieve tensions that are created as a result of confinement. Hence, art is necessary for the mental health of prisoners. Prison arts education helps inmates to develop a disciplined work ethic and allows them to enjoy a greater sense of self-worth, competence and personal accomplishment. Brewster (2015) also believes that art educations in prison are providing inmates with life effectiveness skills that are the essential building blocks for success in academic studies, and in life after prison.

Art in prisons can also be considered a leisure activity for the inmates. Art studies programs have an important goal to provide prisoners with a constructive leisure-time activity to help them relieve tensions that are created as a result of confinement. Hence, art is necessary for the mental health of prisoners. Prison arts education helps inmates to develop a disciplined work ethic and allows them to enjoy a greater sense of self-worth, competence and personal accomplishment. Brewster (2015) also believes that art educations in prison are providing inmates with life effectiveness skills that are the essential building blocks for success in academic studies, and in life after prison.

To conclude this paper which addresses the topic of post-secondary art education in western Australian prisons and the advantages of these courses on the prisoners and society, one would state that it has an overall positive effect. Giles (2016)’s study has determined that art studies seems to indeed be the pathway to help further the education of prisoners who had a poor educational history. Prisoners who took art classes do have a higher rather or recidivism and unemployment. This is do which kinds of prisoners usually end up taking art classes as opposed to non-art classes as mentioned previously. The absence of continued participation in art studies after prison life may have a negative impact on behavior, so it is best that prisoners continue making art after their release. There was also a slower rate of exit from income support for those prisoners who did study art, and this is because Paid work as “an artist” is not as forthcoming as employment as “an accountant” or “a bricklayer”. Same trend is seen in non-incarcerated art graduates. For we live in a society that has yet to value art as a real profession. Overall this study has shown that art studies are best when combined with other courses to set the education pathway. Art studies therefore fundamental to help the personal transformation and successful community reintegration of prisoners after their release.

References

Brewster, L. (2015). Prison fine arts and community college programs: a partnership to advance inmates life skills. New Directions for Community Colleges 170, 89-99.. DOI: 10.1002/cc.20147

Giles, M., Paris, L., & Whale, J. (2016). The role of art education in adult prisons: the Western Australian experience. INT Rev Educ 62, 689-709. DOI 10.1007/s11159-016-9604-3

Giles, M., Paris, L., & Whale, J. (2016). The role of art education in adult prisons: the Western Australian experience. INT Rev Educ 62, 689-709. DOI 10.1007/s11159-016-9604-3

Proudly powered by Weebly

- Sinthia Cousineau

- Ceramic Art

- Drawings

- Paintings

-

Photography

-

Art Education

-

Art & Adolescence

>

- Mural Project >

- Lesson: Eco Art

- Lesson: Decorating Fabric

- Lesson: Zentangles & Patterns

- Lesson: Social Media, consumerism & war

- Lesson: Bag Sculptures & Positive Body Image

- Lesson: Caricatures & political activism

- Lesson: Canadian Landscapes & Group of Seven

- Tattoo Art & Meaningful Images

- Lesson: Stenciling Street Art

- Lesson: Plaster Figures (grade 7-9)

- Photoshop Lesson

- Lesson: Value Scales

- Lesson Plan: Video Art

- Lesson Plan: Sound Art

- Lesson: GIF Project

- Lesson: Mashup Videos

- Art Education & Older Adults >

-

Art & Children

>

- Collage & other art Activities >

-

Drawing Activities with Kids

>

-

Pencil, Markers and Coloring

>

- Introductory Lesson

- Introduction Lesson: Egyptian Name Cartouche

- Reptile Zentangle Drawing >

- Illustrated Names

- Symmetrical Name Creatures

- Drawing from Autumn Still-lives

- Grid Drawing Technique

- Lesson: Alliteration Drawing

- Drawing: 3D Hands

- Leaf Drawing Collage

- Ancient Egypt Art

- Collaborative Doodle

- Drawing: Hidden Emotions Behind the Mask

- Scribble Drawing

- Drawing : Word Art

- Lesson Plan: Renaissance Invention Scroll

- Lesson: La Bande Dessinée

- Lesson: Optical Illusions

- Oil Pastels >

- Chalk & Soft Pastel >

- Charcoal >

-

Pencil, Markers and Coloring

>

-

Painting Activities with Kids

>

-

Acrylic Painting Lessons

>

- Acrylic Pouring

- Australian Dot Painting

- Blow Paint Technique

- Bubble Wrap Painting: Bee

- Pointillism Painting

- Funky Easter Rabbit

- Lesson: The Color Wheel

- Monochromatic Painting

- Painting: Birch Tree

- Leaf Painting

- Pumpkin Painting

- Painting: Rock Painting

- Squeegee Painting Technique

- Origami Inspired Painting

- Coffee Art

- Watercolor Activities >

-

Acrylic Painting Lessons

>

- Mixed Media Activities with Kids >

- Types of Art >

- History Lessons

-

Art & Adolescence

>

-

Art Therapy

- 3D Art & other mediums

- Videos

- Contact Me